East India House, Leadenhall St., drawn by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, c.1817

Willoughby Wallace Hooper was born in London in 1837 and by the age of sixteen he became a writer in the East India Company. A writer was a junior clerk at the lowest level who took minutes, recorded the entries in ships’ logs, assisted the directors and learned the business of the EIC from the ground up. By this time the power of the EIC was waning, to be completely destroyed by the Indian Mutiny of 1857. With the passing of the Government of India Act in 1858 the Crown took over its rule in India and by 1874 the Company was dissolved and its holdings and armies were then controlled by the British government. Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India in 1877, just in case the sub-continent was under the impression it had escaped foreign rule.

Hooper joined the 7th Madras Light Cavalry in 1858 and rose through the ranks until he was made a full colonel in 1884. Throughout his time in India he was an obsessive photographer, as much as one could be while lugging around a large Victorian camera and tripod. He contributed to the eight volume set, “The People of India” , published in parts from 1868-1875, and photographed the Madras Famine from 1876 to 1878.

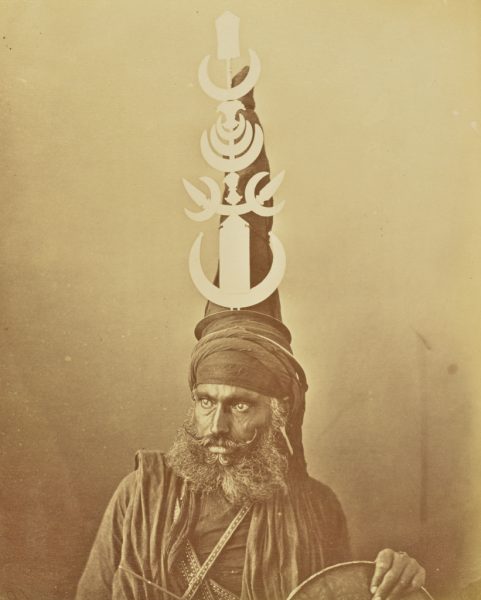

Portrait of a Nihang or an Akali, W. W. Hooper, ca 1870; Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

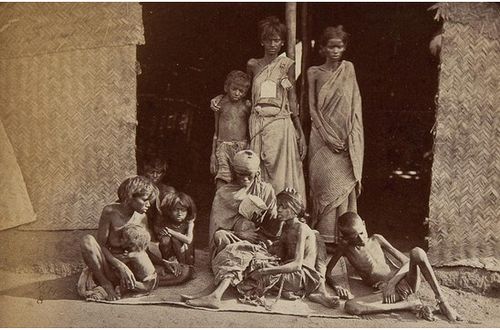

Famine victims, Madras

1876-1878; courtesy of Bloomsbury Auctions – London

I believe that while excelling at the static studio portrait, Hooper wanted more. He wanted to capture the moment; the moment a gun is fired, the moment a man takes his last breath as he dies from starvation. He is described as rushing into battles with his camera and tripod:

“It is related of him that on one occasion when a sepoy went shooting at large at his officers and comrades, he ran out with a photographic apparatus and brought it to bear upon the sepoy, who was in the act of taking aim at him. The homicidal soldier was struck at the instant by a bullet from another sepoy, and Colonel Hooper obtained his negative.”

The desire to seize the moment in an image is not a new one. In the 19th century the Impressionists tried to catch the essence of changing light. The 17th century painter, Caravaggio, stunned the cognoscenti in Rome with his Conversion on the Road to Damascus; his depiction of Saul’s tumble from his horse, his blindness, and his reaching out for salvation is a transformational moment in St. Paul’s life.

The Conversion on the Road to Damascus by Caravaggio, 1600; Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

It was this desire to capture a transformational moment which led to the sensational scandal of Willoughby Wallace Hooper’s dacoit photo.

Newly promoted to Provost Marshall with the Burma Expeditionary Force he sails to Burma in 1885 for what will be the Third (and final) Anglo-Burmese War. The troops commandeer ships from the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company and steam up the river to Mandalay, encountering little opposition.

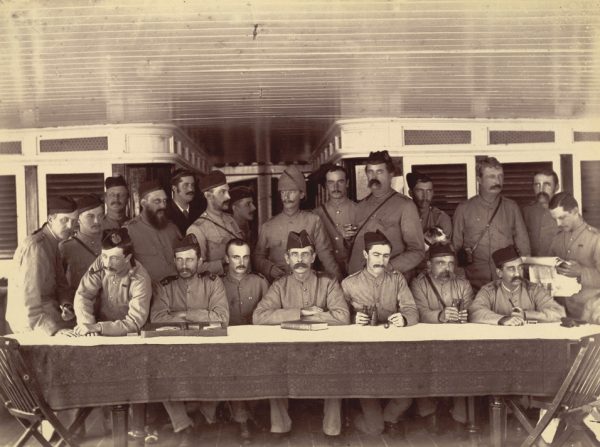

Group of officers taken on board the Irrawaddy Flotilla Co’s Steamer “Irrawaddy” while advancing up the river. W. W. Hooper 1885; British Library

Once disembarked at the Royal City in Upper Burmah, a minimum number of shots are fired, the city taken, the enemy’s arms confiscated and a few days later, King Thibaw and his Queen are banished to Ratnagiri in India.

Arrival of the Expedition at Mandalay on the 28th Nov. 1885; British Library

A Print from a Negative (found in the Palace) of King Theebaw, Queen Soopy-a-lat and her sister; British Library

The fierce fighting was now about to start, with rebels loyal to the country waging guerrilla warfare for a good five years. Some of these soldiers weren’t always polite to surrounding villagers and would often take by violence what they wanted in the way of arms, food and other supplies. The British described them as “dacoits”, a particular and political term. From “Hobson-Jobson,” by Henry Yule and A.C. Burnell, 1886:

“Dacoit, dacoo, s. Hind. … a robber belonging to an armed gang. The term, being current in Bengal, got into the Penal Code. By law, to constitute dacoity, there must be five or more in the gang committing the crime.”

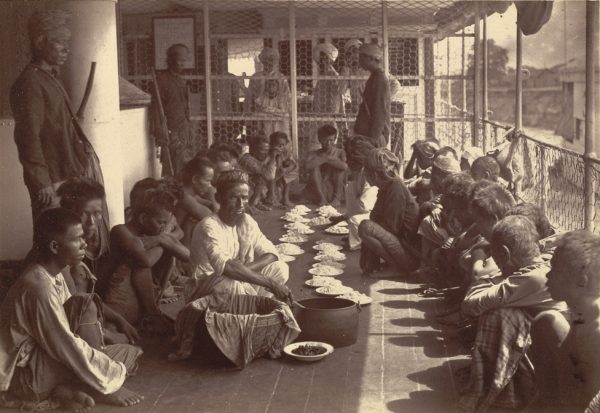

A gang of Dacoits being conveyed down the river from Mandalay to Rangoon on board one of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company’s steamers. W.W. Hooper 1886; British Library

When the British captured armed gangs, they were all considered dacoits, despite many being just villagers hiding in the jungle. At that time, a man in Burma was not considered a man unless he had his “dah” with him; a long, broad, razor sharp knife in a sheath slung over his shoulder. He used it for everything from slicing fruit to chopping down bamboo. It was practically an extension of his arm and although rarely used for any violent purpose, the British had a perfect excuse to inflict the ultimate punishment on any armed group they caught. And they did, just to set an example.

A dacoit group was before the firing squad where Hooper was stationed and set up his camera nearby. There are many pictures of this subject from the past up to the present: the prisoners tied to posts or not, the execution squad poised with their rifles, the aftermath of the slumped bodies. Goya painted this subject in his “The Third of May 1808.”

The Third of May 1808; Museo del Prado, Madrid

They are disturbing because we know what is about to or has just happened. Hooper, though, wanted an unconventional shot and approached it with a scientific frame of mind. The order goes out, “Ready, Present….” But what’s this? Hooper interrupts. He needs to adjust his camera. The calibrations are made, the order to fire is given and Hooper takes the perfect shot of the bullets striking the slight bodies of the Burmese dacoits.

A group of Dacoits captured near Mandalay. W.W. Hooper 1885; British Library

As inured to violence as the soldiers in the BEF were, word of what happened got back to London. It was as shocking to people then as Isil beheading videos are today. The Secretary of State, Lord Randolph Churchill, ordered a court of enquiry. Hooper was reprimanded and given a reduction in pay. It did not seem to hurt his career in the army. He went on to publish “Burmah; a series of one hundred photographs” in 1887 and retired in 1896, dying in England in 1912.

The most remarkable thing to come out of the scandal was the description of it by Grattan Geary in his book, “Burma, after the conquest” London, 1886. I quote some of it here to show his very modern opinion of the Scandal of Willoughby Wallace Hooper, and to show how little the world has changed.

Excerpt pp 241-244, (bold type my own):

“The second instance which may be adduced is that in which the too curious use of the photographic camera added an unseemly element to military executions in Mandalay. Being desirous of getting photographs of the prisoners’ attitudes and expressions at the moment the bullets struck them, the Provost-Marshal set up a photographic camera in a convenient position when the dread words of command, “Ready! Present” were given. The discharge was then delayed for a few minutes while the camera was brought to bear on the doomed men; the focus attained, the signal was given, the bullets struck the waiting men; the negatives were secured. This procedure probably did not add perceptibly to the suffering of the men expecting momentarily the fatal bullets; but there is something unpleasant and almost sinister at the coolness and deliberation with which the action of the tragedy was suspended in order that a scientific record might be taken of the effect, physical and moral, of the shock of bullets, on the persons of defenceless and despairing men. Lord Dufferin at Calcutta and the Ministers in England shared the indignation of Mr. Bernard, when they came to know what had been done. The then Secretary of State, Lord Randolph Churchill, at once telegraphed instructions that grave and immediate action should be taken with regard to the officer concerned. His successor ordered that the Provost Marshal should be tried by Court-martial. But no one supposes that statesmen and administrators, accustomed to recognise and respect the rights of humanity, would fail to reprobate acts of the kind. The fatal thing is that such acts under certain circumstances become inevitable under a natural law, which ordains that the practice of cruelty makes even merciful men cruel, dulling the moral sense until it is impossible to draw the line with any precision between what is legitimate and what is not.

It is fair to say that Colonel Hooper has the reputation of being a very good officer, and that the desire to photograph the Burmese when struck by bullets is attributed, not to any inhumanity, but to what may almost be regarded as a passion for securing an indelible record of human expression at the supreme moment. It is related of him that on one occasion when a sepoy went shooting at large at his officers and comrades, he ran out with a photographic apparatus and brought it to bear upon the sepoy, who was in the act of taking aim at him. The homicidal soldier was struck at the instant by a bullet from another sepoy, and Colonel Hooper obtained his negative. At the battle of Minelah the gallant officer carried his camera under fire, so that it might be available for the record of any exceptional incident.

The photographing of the men shot at Mandalay under the circumstances mentioned was undoubtedly reprehensible. It created a bad impression, from which Colonel Hooper must be prepared to suffer in public opinion. But it is open to doubt whether there is not something very pharasaical in the spirit which revolts at the operation of photographing a batch of men at the moment of their execution, when their execution in batches is accepted as an ordinary incident in the subjugation of a conquered people. If all the men who were shot were dacoits, or had committed any moral offence other than that of hazarding their life in a lost cause, the shooting would be righteous as well as necessary, but, speaking generally, the executions in such cases are exemplary, and not punitive. It is the custom to close the eyes and the ears to the real nature of the “salutary severities” which are sparingly alluded to in the narratives of military operations in a vanquished country. It would be a great gain to the cause of humanity if there were more Colonel Hoopers, who would focus and fix and make widely known, every horror which it is the custom to slur over in referring to incidents of the kind. If people at large realised with anything like exactitude, the real nature of the price which subjugated populations pay for the blessings of civilisation, sounder views on such subjects would perhaps become more prevalent. As has been said above, if the severities produced always and everywhere the tranquillising effects which are generally expected from them, it might be a duty to acquiesce, as it is the duty of a surgeon to inflict pain as the price of an ultimate good.”

Some of King Theebaw’s Guards at the East Gate of the Palace enclosure, [Mandalay], the day we entered. W.W. Hooper 1885; British Library

References:

Luminous Lint

John Falconer at Luminous Lint

The British Library

Wikipedia